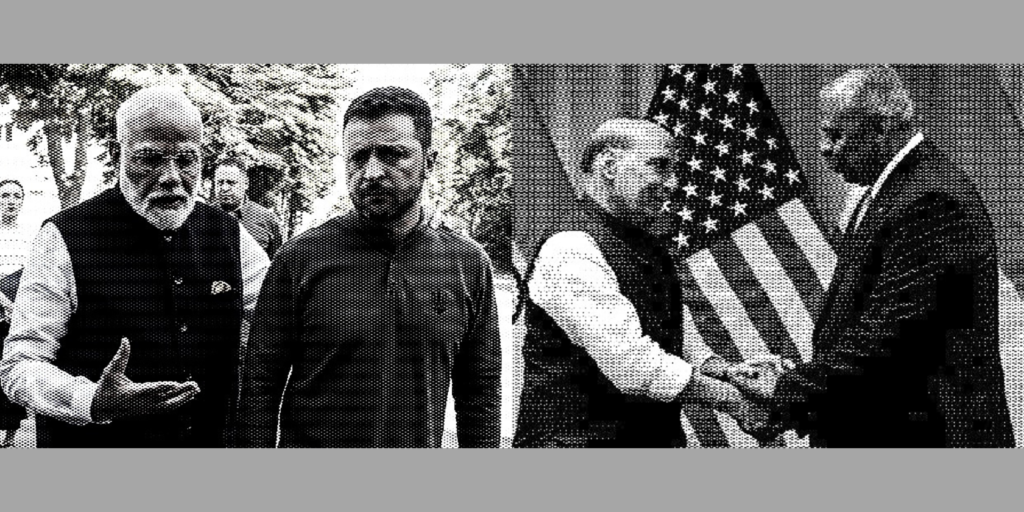

On 22 August, India’s Defence Minister, Rajnath Singh, began a four-day visit to the US, parallel to the Indian PM’s visit to Ukraine. Singh’s visit expectedly furthered the defense relationship between both states with new agreements, given that few crucial agreements remained to be signed since the launch of the US-India Defense Industrial Cooperation Roadmap in 2023. More importantly, the long delay in the supply of General Electric’s F-404 engines to India has consequently delayed HAL’s supply of the Tejas Mk1A to the Indian Air Force. Singh’s visit was expected to address this issue, as the poor implementation of older agreements has set a negative precedent for the flurry of newer deals between New Delhi and Washington. The visit underwrites the well-evident desire in both New Delhi and Washington for a broader defense relationship. However, couched within this larger desire, it also acts as a new barometer for Indian foreign policy – a mix of tactical decisions with new risks along with strategic shifts.

Strategic tilts and tactical maneuvers

The Defence Minister’s visit to Washington was another checkpoint in India’s more significant tilt westward in recent weeks and months, given the reported “advancement” of critical agreements such as a Security of Supply Arrangement (SOSA) and a legally binding Reciprocal Defense Procurement Agreement. Singh followed up on crucial aspects of the 2023 US-India Defense Cooperation Roadmap, securing potential collaboration to advance India’s underwater capabilities, with the visit being followed by the Indian Army sanctioning an emergency procurement of another large batch of Sig Sauer 716 rifles. Evidently, the visit’s outcomes bolstered the base of the defense relationship that has been steadily laid across the last decade through iCET, INDUS-X, and key ‘foundational agreements’ – LEMOA in 2016, COMCASA in 2018, BECA in 2020.

This alone is reflective of India’s strategic choices with the West at large, furthered even more in the first 100 days of PM Modi’s third term. For instance, India’s advancing of cooperation with Japan, substantiated during the 2+2 dialogue on 20 August, represents New Delhi’s desire to positively exploit Japan’s own rejuvenation of its defense industry. Moreover, ahead of the upcoming Malabar Exercise, the Indian Air Force conducted its first ever multinational air exercise – with major Western air forces as the primary participants (Russia declined the invitation due to commitments in Ukraine).

Beyond the outcomes on defense cooperation, Singh’s visit (and its timing) also reflects India’s tactical approach to foreign policy, while its strategic shift is underway. President Biden’s phone call with PM Modi after both visits, commended his “message of peace…and humanitarian support for Ukraine”. The Prime Minister’s Kyiv visit was a tactical decision by New Delhi to mitigate the apparently spiraling after-shocks of PM Modi’s Russia visit and featured new characteristics of risk-taking. PM Modi not only had to confront the physical impact of Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian civilians (especially children), but also repeatedly craft new language to avoid testing Russia’s red lines. The Prime Minister asserted that India was “not neutral” and had chosen the “side of peace”, and concluded a host of bilateral agreements on high-capacity development projects, agricultural cooperation, etc. Domestic media and analytical reactions to PM Modi’s Kyiv visit have been colored by both critical and vindicative narratives. However, there is acknowledgement across the board that the Ukrainian President continued to attack India’s purchase of Russian oil, tweeting after Modi’s return to India, that such purchases were funding his (Putin’s) aggression against Ukraine. The President’s statement that Putin did not respect India and that he would prefer India to side with Ukraine instead of ‘balancing’ between Kyiv and Moscow has been seen as disregarding of Indian sensitivities and core foreign policy positions. Amidst perceptions of Ukraine throwing in surprises during and after the visit, some analysts wondered if the visit was a mistake in the first place.

The Indian government, however, steered away from frontal and proportionate reactions. On being asked whether India’s import of Russian energy had featured in the discussions (given Ukraine’s strong position against it), India’s External Affairs Minister (S Jaishankar) asserted that it did not feature “at great length” and India explained to the Ukrainian side “the energy market scenario” along with the importance of keeping oil prices stable. Arguably, with both Modi’s embrace of Zelenskyy and Jaishankar’s cultural rationale for such expressions, India also sought to dent the focus of Western criticism of the Indian PM’s Moscow visit – his embrace of Putin as Russia bombed a Ukrainian children’s hospital. Jaishankar’s press conference consistently referred to PM Modi’s oft-repeated phrase that “this is not an era of war”. The tactical nature of India’s decision-making has also been evident in India carving out a new role of “passing messages” between Russia and Ukraine – diverting the conversation away from mediation. The Prime Minister’s call to President Putin, after his return from Kyiv focused on war termination and the importance of dialogue and diplomacy.

Future of India’s Global Engagement

For India, its tactical choices vis-à-vis Russia-Ukraine (Modi’s Kyiv visit) are cushioned by the substantial aspects of its Westward tilt (Singh’s Washington visit). More importantly, it relies on the latter to ensure that its concessions are symbolic, rather than substantial – typified by its new language and variations of calls for peace. This at once avoids criticizing Russia and avoids concessions to Zelenskyy’s calls for Russia’s unilateral responsibility for conflict termination. India’s specific choices vis-à-vis Ukraine remain unchanged. For instance, despite India’s support for Global Peace Summits on Ukraine, it still refrains from endorsing the outcomes of the older Switzerland Summit, where Russia was not a participant. On being asked whether India would urge Russia to participate in future Summits, Jaishankar stated that “that’s really not an issue for us to take a call”, focusing instead on India’s NSA-level participation while also cautioning that India does not necessarily agree on all outcomes from such Summits.

While the Defence Minister’s visit naturally focused on furthering the defense relationship between both states, its ancillary effect is the normalization of the new dynamic in India’s ties with the West; it resembled visits of Indian officials to Russia in the past – with a strong focus on buying new defense equipment. In any case, Indian and American firms have long had crucial tie-ups for defense co-production due to India’s off-set policies that require the setting up of production facilities in India. For instance, Tata’s Joint Ventures with Boeing and Lockheed Martin in Hyderabad are the sole global producers of fuselages for Apache helicopters and empennages for C130 transport aircrafts, respectively. The ripple effect of greater cooperation in newer areas (such as the repair of USNS ships in Indian ports) has generated an interest in such partnerships by other Western states (with Japan asking for similar arrangements).

In the months ahead, India will prepare for a Quad summit and host the Malabar Naval exercises. In a recent phone call, PM Modi had ‘discussed’ the Quad with his Australian counterpart, striking a symbolic note. At the same time, India’s enthusiasm towards the upcoming BRICS summit in Russia is likely to be strongly limited as its agenda shapes up to be exclusionary. With gradual appreciation of Russia’s drift away from India, Delhi may have added additional weight to its tilt towards the West.