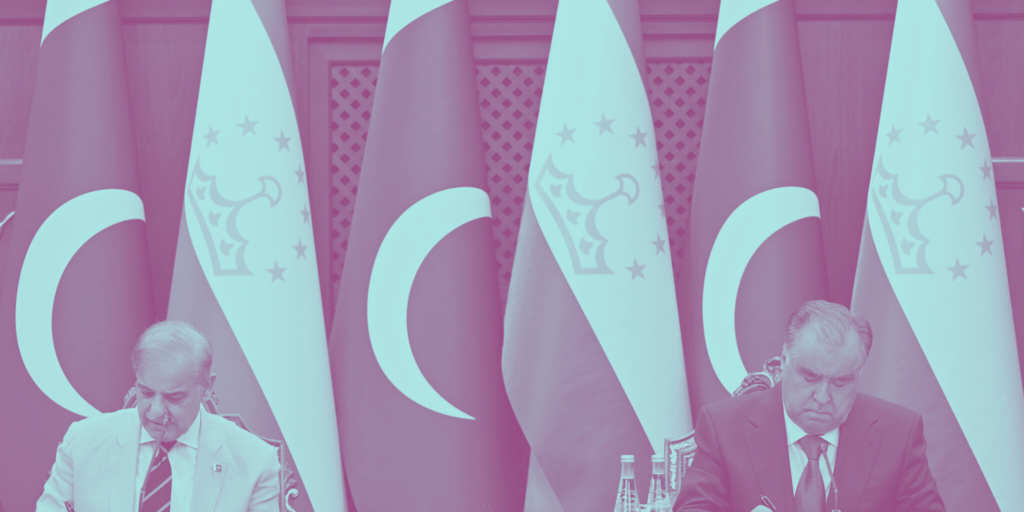

On 3 July, Pakistan PM Shahbaz Sharif led a delegation to Tajikistan, meeting the Tajik PM Qohir Rasolzada and senior officials including military and intelligence, to discuss bilateral issues and interests. The joint declaration expanded on agreements made during the Tajik President’s December 2022 visit to Pakistan, when Tajikistan held the SCO chairmanship. It reaffirmed both countries’ commitment to cooperate in various sectors, with a particular emphasis on trade, an area both nations consider underexploited. In the 2024 Astana Summit of the SCO, Tajikistan was especially vocal on the issues of drugs and arms flowing from Afghanistan; Dushanbe reiterated its proposal for a new “security belt” around Afghanistan, with an increase in clashes between security forces and drug smugglers at the Afghan-Tajikistan border. However, while Pakistan-Tajikistan ties are old and cross-cutting in terms of areas of interest, Afghanistan has been increasingly emerging as a salient point of convergence.

The evolution of Tajikistan-Pakistan ties especially vis-à-vis Afghanistan is significant because of their cooperation against the Taliban. This is a relatively new and growing factor with implications for India’s interests in Afghanistan and Central Asia, at large.

Sharing a Twin-Taliban problem

On the last day of 2023, the Taliban voiced concerns over foreign militant activity from Tajikistan and Pakistan in particular, claiming to have killed dozens of Tajiks and more than 20 Pakistanis in operations by security forces across that year. In general, the Taliban has been increasing its allegations against Tajikistan and Pakistan for increasing militant activity in Afghanistan. Tajikistan has arguably drawn more confidence to cooperate with Pakistan against the Taliban, from Islamabad’s new proclivity in conducting air-strikes on suspected Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) positions in Khost, Kunar, and other districts, to which the Taliban has usually responded with cross-border fire. Just as Pakistan’s own Taliban problem, the TTP, has grown since the regime change in Kabul, Tajikistan too has long been grappling with the Jamaat Ansarullah (JA), colloquially termed the Tajik Taliban. As the Taliban reneged on its assurances to Pakistan over reducing the TTP’s space to operate in Afghanistan, the TTP has rapidly catapulted itself back to the top of Pakistan’s internal security concerns, amidst its ongoing poly-crisis. However, with Tajikistan, the Taliban barely made any such commitments in the first place, actively co-opting the JA as early as July 2021 and placing its commanders in charge of its Northern border with Tajikistan. This is in stark contrast to the former Islamic Republic of Afghanistan that conducted multiple operations against the JA. Now, the Taliban’s co-opting of Tajik militants has enhanced the operating space for ethnic-Tajik militants of various groups (even those fighting the Taliban), especially along Tajikistan’s particularly vulnerable, extensively mountainous, border with Afghanistan. This was especially evident in recent high-profile attacks by the Islamic State Khorasan Province in Iran and Russia.

The Tajik military, historically considered the weakest in Central Asia, has so far avoided direct conflict with the Taliban, including cross-border strikes. However, Tajikistan likely views Pakistan’s military actions in Afghanistan favorably, potentially opening doors for future collaboration between Tajikistan and Pakistan. In any case, Tajikistan keeps its forces at high combat readiness, having mobilized the highest number of troops in its history for a border exercise as instability was increasing in Afghanistan in July 2021.

Connectivity as a pressure point

Since the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in 2021, Tajikistan has been largely alone in the intensity of its criticismof the Afghan Taliban that it asserted was “formed by oppression”. This intensity had unsettled even Pakistan (read: Imran Khan) which in 2021 was largely celebratory of the Taliban’s return. Much to the Taliban’s chagrin, Tajikistan continues to host officials from the deposed democratic Afghan government, and the Ahmad Massoud-led National Resistance Front (NRF). Dushanbe also hosts the Herat Security Dialogue which the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan’s officials moved from Herat to Dushanbe after 2021 and continues to resist the Taliban’s efforts at placing its Ambassador in Dushanbe. Given Dushanbe’s vigorous support of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance in the 1990s, its historic opposition to the Taliban (and its strong measures against the group in 2021) distinguishes it from Pakistan’s current unease with the Taliban. For Islamabad, the breakdown in relations is a function of the Taliban’s assertiveness at the Durand Line and support of militant groups, arguably forcing it to hunt for tactical points of pressure against Kabul. For Dushanbe, the concern is strategic and long-term, with more enduring sources of mistrust. Presently, it is the overlapping interest in modifying the Taliban’s behavior with Pakistan that has added a new contemporary dimension to bilateral ties.

Evidently, shared short-and-long term concerns over the Taliban in Afghanistan from this point has also led both states to revive conversations over the Quadrilateral Traffic in Transit Agreement (QTTA) that provides Central Asia’s Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan access to Pakistani ports through China, by way of circumventing Afghanistan. While the QTTA was undermined by the erstwhile Islamic Republic’s openness to Pakistan-Central Asia connectivity, even by 2021, a study by Islamabad’s Institute for Policy Studies showed that Afghanistan remained reluctant to grant Pakistan access to Central Asia, especially as Kabul demanded reciprocal access to Indian goods.

Looking at Kabul from Islamabad and New Delhi

Pakistan has had a long-standing desire to strengthen its ties with Central Asian countries. It’s ‘Vision Central Asia’ seems to be among the few policies conceptualized under the Imran Khan administration, now also actively promoted by Shahbaz Sharif. However, its approach to connectivity with the region has almost invariably been through Afghanistan, not least due to the tyranny of geography (Pakistan and Tajikistan are separated by Afghanistan at all points).

The QTTA was more exception than norm. Indeed, until the recent destabilization in Af-Pak ties, Afghanistan featured strongly in Tajikistan-Pakistan trade ties, with the Tajikistan Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement of 2022 relying on transit points through the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (the agreement’s text uses the older name for Afghanistan arguably due to Dushanbe’s sensitivities). In June 2023, Pakistan sent its first shipment to Kazakhstan via the QTTA, a route conceived in 1995. This nearly 30-year delay in utilizing the route indicates Pakistan’s revised strategy. It aims to develop alternative transportation links that bypass Afghanistan, potentially serving as leverage against the Taliban. That the shortest and most efficient routes remain through Afghanistan is undeniable; one of Pakistan’s largest logistics firms (TCS) completed an unprecedented test runof moving shipments from Karachi to Baku via Afghanistan just 20 days before Sharif’s visit to Dushanbe. Hence, the extent of Tajikistan-Pakistan cooperation against Taliban-ruled Afghanistan is more contingent on Islamabad’s ties with Kabul, than Dushanbe’s.

India, which has been teasing improved ties with the Taliban (including as leverage against Pakistan), views a stable, more moderate, and inclusive government in Kabul as a necessity, especially for security reasons. Indian firms have still not returned to Afghanistan despite the government’s overtures. India’s leverage through corridors such as the INSTC has been limited thus far due to Tajikistan’s issues with trade through Iran, notwithstanding recent progress made under the late Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi. Hence, the scope and scale of Tajikistan-Pakistan cooperation in the near future will determine how India’s own interests are affected. Despite tensions with Pakistan, if the Taliban takes stronger action against militant groups, it would enhance security and stability for all regional actors in Afghanistan. This would also benefit India, which has recently shown greater interest in the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure. Moreover, Delhi will have no reason not to encourage the Taliban to demand overland trading access to India in exchange for similar rights to Pakistan for trading with Central Asia. More importantly, India will closely monitor the developing comprehensive cooperation between Pakistan and Tajikistan, particularly its security aspects.

Since the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in August 2021, New Delhi has shed its older position of non-engagement with the Taliban, and incrementally but slowly increased its level of contact, while refraining completely from expressing any support (at least publicly) to the Tajikistan based NRF. This arguably has less to do with any new-found comfort in dealing with the Pashtun dominated Taliban over the non-Pashtuns, and more to do with the present reality on the ground – that unlike the late 1990s when the Ahmad Shah Massoud led resistance was a credible armed actor among several which maintained control over Northern Afghanistan, the Taliban today has forced the NRF to move out, despite an initial burst of resistance in the Panjshir Valley that was nipped in the bud. For Pakistan however, any indications of a swing in its own position toward the non-Pashtuns are lacking. Even while its ties with the Taliban are currently in a downward spiral, Islamabad’s only incentive to make any future overtures towards the non-Pashtun opposition would be to find an additional pressure point to force the Taliban into concessions that would stabilize Kabul-Islamabad ties, rather than any belief that the resistance can affect any changes on the ground.